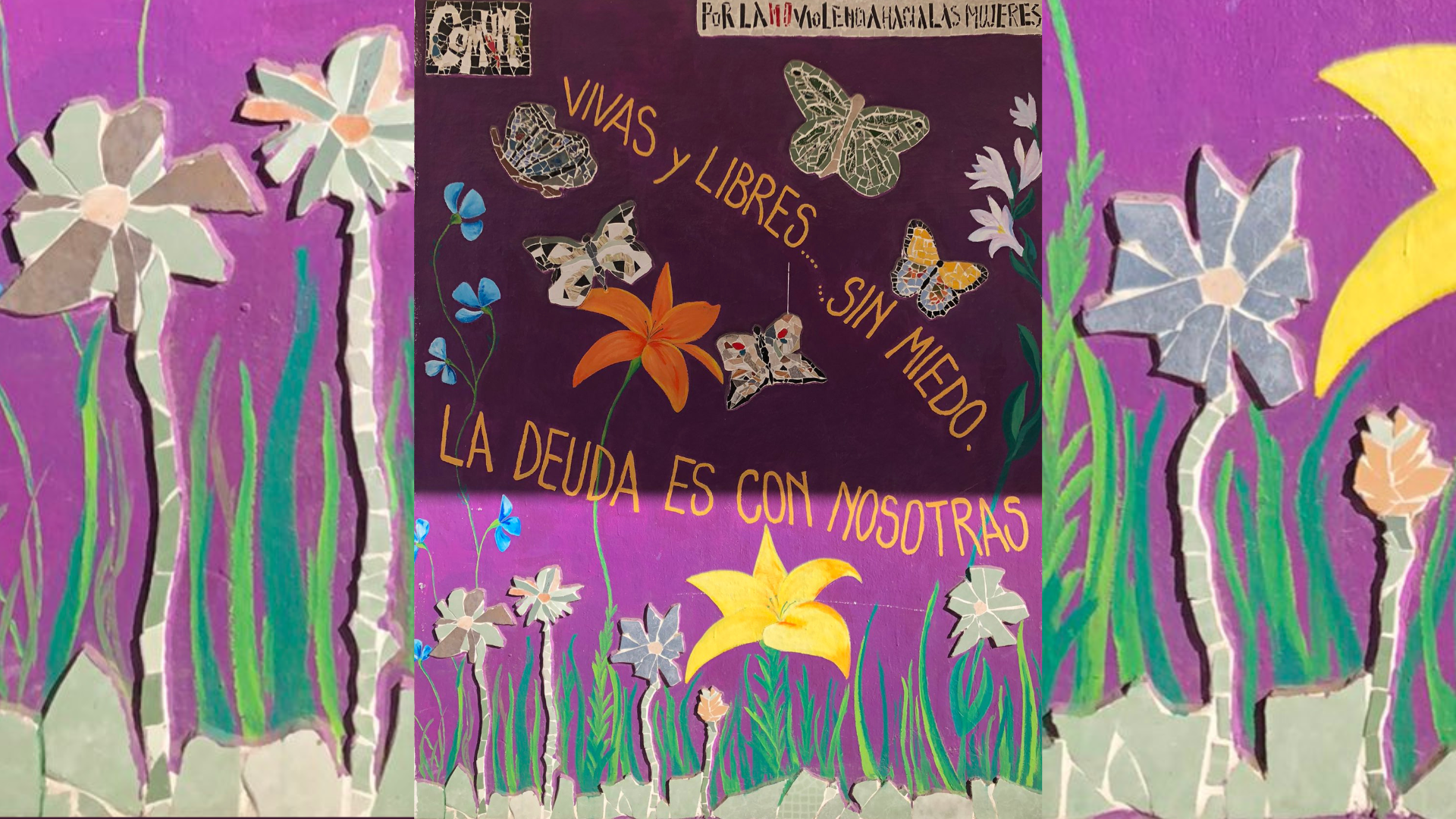

Photo credit: Melisa Slep

By Rishita Nandagiri and Lucía Berro Pizzarossa

Discussions about abortion tend to be dominated by considerations pertaining to medicine (e.g., “safety”) and law (e.g., “legality”). Medication abortion — misoprostol alone or in combination with mifepristone — has dramatically shifted these discussions. Brazilian women used misoprostol to self-manage their abortions in the 1980s, galvanizing Latin American and transnational feminist efforts to share knowledge and organize access to pills. In 2005, these medicines were added to the WHO’s Essential Medicines List. Self-managed abortion (SMA), which includes self-sourcing of abortion pills, self-diagnosis, and management of abortion processes and post-abortion care outside formal health systems, unsettles traditional understandings of what an abortion is, where and how it can (or should) occur, who a provider is, and what a “safe” abortion is.

In April 2024, Polish activists from Abortion Without Borders (AWB) invoiced the Sejm (Polish parliament) €11.5 million ($12.4 million) for the financial costs and reproductive labor associated with providing abortion access, resources, and care for Polish residents. AWB, an initiative by nine feminist organizations working across multiple countries, was founded in 2019 to provide information, support, and funding for abortion in Poland, either via pills or travel for in-clinic care abroad. Poland has some of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe, which many describe as constituting a de facto ban on abortions. Ministry of Health statistics report Polish hospitals conducted only 161 abortions in 2022. In contrast, Polish non-governmental organizations estimate that, every year, 120,000-150,000 abortions are obtained via pills or procedurally.

The Abortion Debt

Activists, including Natalia Broniarczyk (Abortion Dream Team), Kinga Jelińska (Women Help Women), Justyna Wydrzyńska (Kobiety w Sieci and Abortion Dream Team), and Mara Clarke (Supporting Abortions For Everyone), invoiced parliamentarians prior to a parliamentary debate on abortion. Their invoice, for the “Polish abortion debt,” accounted for costs associated with abortion with pills ($6,153,000) and abortions performed in clinics/hospitals in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and other countries ($6,314,694).

The “Polish abortion debt” highlights the state’s abdication of responsibility for care provision. It underscores how the state outsources abortion care to individuals, feminist providers, and in some cases, other countries and their health systems. Poland is not the only country that owes a debt — financial, reproductive, and informational — to feminist activists and collectives and abortion seekers. Before its 2018 referendum, Ireland was noted to outsource abortion services to other states and rely upon transnational networks to access abortion pills. Similarly, Malta has been described as outsourcing its abortions to charities and other states.

Poor healthcare investments also shift the responsibility to seek, access, and pay for care to individuals. In India, abortion has been legal since 1971 and should, according to Ministry of Health guidelines, be provided for free at public health facilities. However, many public facilities do not offer abortion services, may not have trained staff or the required equipment, or may impose additional requirements that stigmatize or shame abortion-seekers. Inadequate investment contributes to lack of service provision, often requiring abortion-seekers to pay out-of-pocket, increasing financial burdens and placing many at risk of debt. This is particularly the case for those living in places where abortion is criminalized.

By claiming a debt owed, AWB activists are actively reframing and reimagining what abortion, reproductive labor, and reproductive care mean and subverting dominant approaches to abortion. An “abortion debt” is therefore both a debt owed by governments and experienced by individuals..

Revolutionary Acts, Abortion Reimagined

Beyond providing an immediate solution to restricted or unavailable abortion services, SMA movements reimagine abortion care. When states use archaic laws adopted in 1861 (UK) or 1864 (Arizona, USA) to prosecute people for procuring or attempting abortions in 2024, activists respond with hotlines, websites, and accompaniment networks — parallel processes that push the boundaries of legality, while simultaneously offering alternate practices and visions for what abortion care can look like.

In Chile, a feminist protest sign reads “With miso and without permiso [permission]” pointing to the revolutionary power of misoprostol to bypass obtaining “permission” from the state or medical professionals. Similarly, in the Dominican Republic, Chile and Argentina, feminists frame abortion as “deuda de la democracia” (a debt of democracy) because abortion restrictions curtail people’s full citizenship and full ability to exercise their rights and freedoms. In France, constitutional protections for abortion rights are presented as a “moral debt.” These articulations of what is owed to women and pregnant people fracture traditional understandings of how rights are claimed and exercised. Activists’ protests, appropriation, defiance, and subversion all mount a profound critique of governance and the state, but these expressions of dissent are also catalysts for social and political transformation, with the capacity to imagine and create anew.