Egg Donation: A Victory for Reproductive Justice or Another Handmaid’s Tale?

Before the United States election in 2024, Margaret Atwood shared a cartoon illustrating the handmaids from her dystopian novel entering a polling booth in their unmistakable red cloaks and white bonnets. Having voted, they transform into unique individuals, discarding the attire symbolizing their reproductive enslavement.

Published

Author

Share

Before the United States election in 2024, Margaret Atwood shared a cartoon illustrating the handmaids from her dystopian novel entering a polling booth in their unmistakable red cloaks and white bonnets. Having voted, they transform into unique individuals, discarding the attire symbolizing their reproductive enslavement.

One of the central topics of the election campaign was undoubtedly abortion—a key issue in the fight for reproductive justice. However, reproductive justice encompasses far more than abortion. The egg donation industry has expanded into a multi-billion dollar market. While altruism frequently frames their actions, financial incentives are central to attracting many young women to donate—really, sell—their eggs. Upon closer examination, egg donors play a subordinate role despite being essential for the market to function. This post explores the egg market in the U.S. and Europe, shedding light on its implications for the reproductive rights of third parties involved in the process.

The U.S.: A free market model

In the U.S., egg donation operates as an unregulated free market. Compensation varies widely, reaching up to $250,000 in exceptional cases, with an average payment of approximately $7,000. Efforts by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) to regulate this market through guidelines capping payments failed: ASRM attempted to limit donor remuneration to $10,000. However, two donors sued ASRM, claiming the guidelines violated U.S. antitrust laws by constituting price-fixing. In 2015, a settlement agreement forced ASRM to remove the guidelines and refrain from making any recommendations regarding price.

While this proliferation of choices might be seen as a victory for reproductive justice, a closer examination reveals uncomfortable realities shaped by social inequalities. The unregulated market in the United States undeniably gives some women substantial negotiating power. Donors considered “hard-to-find” due to traits like Ivy League education, athletic or musical talents, or specific racial characteristics can command higher fees. However, data suggests that white women are paid up to eight times more for their eggs than Black women. ASRM’s 2016 guidelines proposed not to give additional compensation for specific characteristics such as ethnicity. However, the free market in the U.S. seemed to trump these suggestions, leading to a de facto differentiation in the value assigned to women’s eggs (ASRM 2021), thereby perpetuating existing inequalities.

The European Union: A regulated market in a non-commercial setting

The EU’s approach contrasts sharply with the U.S.’s unregulated market model. The European Court of Human Rights grants the member States of the Council of Europe a wide margin of appreciation regarding the approval of reproductive medicine due to the sensitive moral and ethical issues involved. However, in the EU specific regulations influence their governance where reproductive technologies are allowed: Article 3(2)(c) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights prohibits making the human body and its parts as such a source of financial gain. Similarly, the EU Tissue Directive urges EU member States to ensure voluntary and unpaid donations, a principle reiterated in the new SoHO Regulation. These regulations prohibit financial incentives that improve donors’ financial positions but allow expense reimbursement.

While these rules aim to protect donors, reality often challenges their effectiveness. Spain has become Europe’s egg donation capital, attracting international intended parents. Donors in Spain receive compensation ranging from €800 to €1,300— amounts that exceed the monthly income of many young women in the target demographic. Financial incentives dominate motivations, fostering a thriving market within a system ostensibly designed to discourage it. Similar to the U.S., some donors are valued more highly than others. Clinics actively recruit Eastern European migrants or international students to satisfy the demand for fair-skinned donors, reflecting the phenotypic preferences of Northern European intended parents.

Reproductive (In)Justice

Despite the differing regulatory frameworks in the U.S. and the EU, compensation remains a primary motivation for many donors. For some, the financial incentive is so significant that they expose themselves to health risks and exceed the recommended number of donation cycles. Moreover, the long-term effects of egg donation are poorly studied, raising questions about informed consent.

Nevertheless, just like the reproductive labor of Atwood’s handmaids, egg donation is framed as an altruistic act in both the U.S. and Spain, promoting narratives of sisterhood. Yet, egg donors occupy a subordinate role in the process. The scholar Laura Perler observes an increasing invisibility of egg donors in Spain. Egg donation occurs within a highly technical setting, deliberately avoiding relational language that acknowledges the donor’s role as a genetic mother and downplays the potential significance she holds for the resulting child. This narrative echoes Atwood’s dystopia, where young, fertile women are indispensable for the society of Gilead to function, yet stripped of individuality and reduced to a technical function.

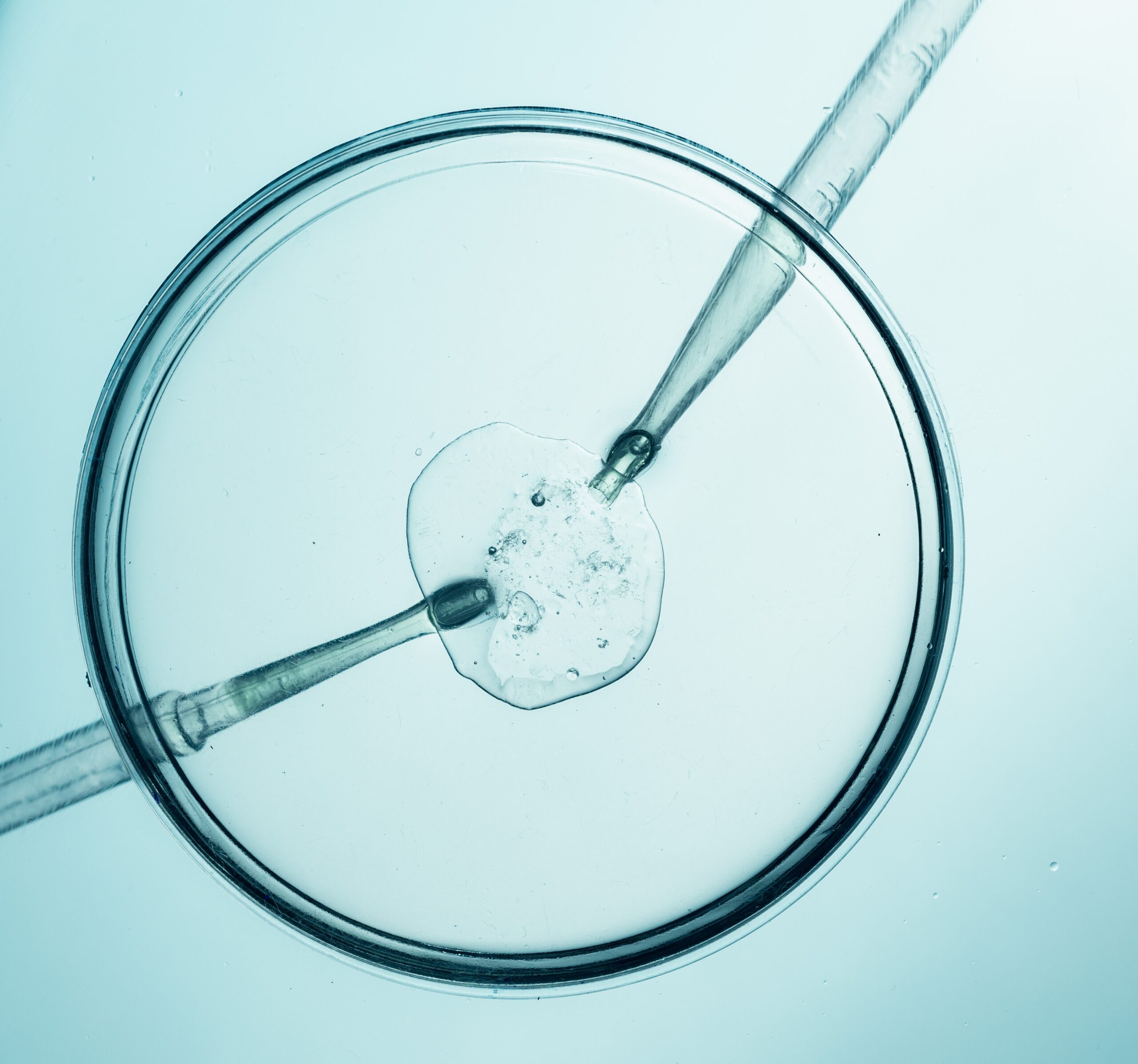

Globally, there is a growing trend toward the privatization and commercialization of fertility clinics. The reproductive market is a multi-billion dollar market with a high annual growth rate. The vitrification method which made it possible to freeze and thaw eggs to preserve them for future use contributes to this growing market and the invisibility of egg donors by depersonalizing the donation process. Synchronizing the menstrual cycles of the donor and the recipient is no longer necessary, and eggs from a single cycle can be used for multiple recipients at different times and places. The vitrification method has led to a significant boom in the egg donation market. While payments or compensation for egg donors remain unchanged, egg banks primarily profit from this development.

Conclusion

The framing of egg donation as an act of sisterhood obscures the subordinate role of egg donors in the donation process, with their contribution often reduced to a purely technical function. Selection criteria heavily influence the process. Women’s eggs are valued differently based on race and other traits, reflecting broader social and economic inequalities. Private clinics exploit these disparities, viewing the egg donation market as a lucrative global growth industry. Although it may not mirror the outright enslavement depicted in Atwood’s Gilead, providing eggs is often framed as a pathway to autonomy for women while simultaneously deepening existing inequalities.