Watch Out! Funding Cuts, Food Safety Surveillance, and Federalism

On July 1, the federal government quietly scaled back its only active surveillance system for foodborne illnesses.

Published

Author

Share

On July 1, the federal government quietly scaled back its only active surveillance system for foodborne illnesses.

The Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) is a partnership comprising three federal health agencies — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Department of Agriculture — and 10 individual state health departments.

For 28 years, FoodNet had been tracking infections caused by eight pathogens. Now it only tracks two: salmonella and a strain of E. coli called STEC.

State officials have relied on FoodNet to address outbreaks and inform policy innovation in food safety. The system’s recent reduction will further strain resource-strapped state health departments and sow confusion among consumers who depend on timely notifications of outbreaks to make informed food consumption decisions.

Federal Cuts to Food Safety

The CDC cited funding as a reason for its slashes to FoodNet, reflecting another instance of disruption to the nation’s food safety programs after the Trump administration downsized the Department of Health and Human Services by 20,000 employees earlier this year. In April, for example, the FDA suspended a proficiency testing program for milk and other dairy products.

For FoodNet, funding cuts meant terminating data collection on six pathogens: campylobacter, cyclospora, listeria, shigella, vibrio, and yersinia. Some of these pathogens can cause severe illness. Every year, campylobacter and listeria are among the top five pathogens contributing to deaths by foodborne illness. Last year, Boar’s Head deli products caused the largest listeria outbreak in over a decade.

Other national surveillance systems are still monitoring for the pathogens removed from FoodNet, such as the CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). But FoodNet is the only system that conducts active surveillance, meaning that health agencies regularly contact clinical laboratories to identify new cases. In passive surveillance systems like NNDSS, the CDC relies on health care providers and laboratories to notify it of new cases, which can result in delayed or under-reporting.

Surveillance Systems and “Foodralism”

FoodNet’s network includes California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, and Tennessee. Although a competitive grant process selected these states, FoodNet sites have turned out to be largely representative of the national population.

Without federal support, it is uncertain whether these states will have the capacity to continue surveilling the pathogens that FoodNet covered before July. While Maryland health officials told NBC that they will continue reporting on all eight pathogens in accordance with state requirements, Colorado health officials indicated that they might lose the ability to maintain their active surveillance efforts.

Beyond creating additional burdens for state health departments, the federal cuts to FoodNet will harm states by stifling their development of food policy.

In a 2018 article, Professors Laurie Beyranevand and Diana Winters coined the term “foodralism” to describe the relationship between the different levels of government involved in regulating food. Because the federal government is slow to address areas of rapid change in the food landscape, they argued for a notion of foodralism that enables states to lead innovations in food policy. For example, they highlighted a California law that addressed growing concerns about antibiotics in food production by restricting antibiotic use in animal feed.

But preemption poses an obstacle to state-driven foodralism, according to the professors. Uncertainty about whether courts will invalidate state legislation on preemption grounds has discouraged states from innovating in the food policy space. As a result, their article called for the FDA to issue guidance rather than binding regulations when faced with rapidly changing food policy problems.

Although federal regulation can stifle the development of state-level food policy, federal surveillance drives it. Experts have used FoodNet data to understand wide-ranging food policy issues, from disparities in foodborne illnesses across social demographics to clinical laboratory testing standards. These lessons are invaluable for state policymakers hoping to advance creative, evidence-based food policy.

Will the Private Sector Save Us?

In the face of reduced federal surveillance and uncertain state responses, some consumers have turned their attention to private grocery retailers that could act as sponsors of food safety.

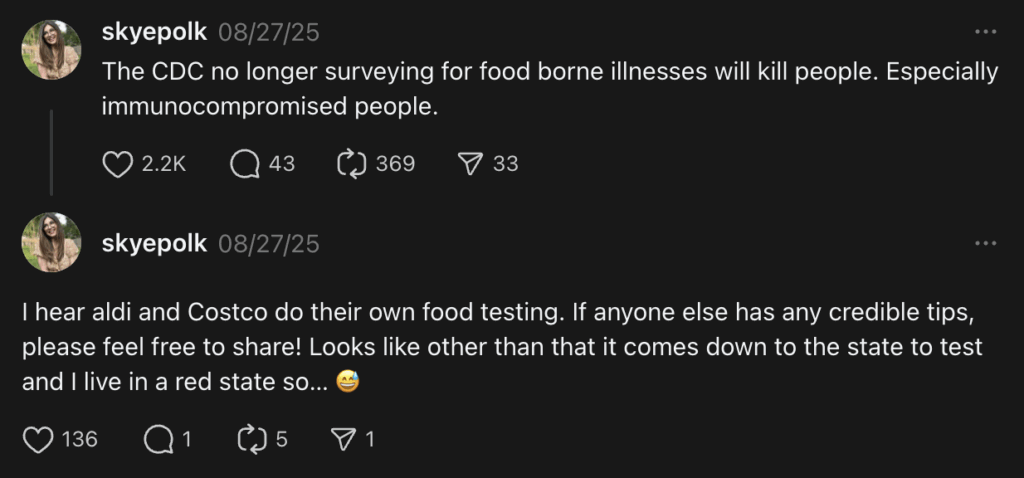

Reacting to news of FoodNet’s cuts, one user posted on Threads: “I hear [A]ldi and Costco do their own food testing. If anyone else has any credible tips, please feel free to share!”

Many large retailers require their upstream suppliers to have third-party food safety audits and conduct internal testing, but challenges remain:

- First, these practices may not be entirely risk-free. In 2013, the owners of Jensen Farms were criminally prosecuted for a listeria outbreak that led to 33 deaths, but they also sued a food safety audit firm called Primus Labs, which they alleged acted negligently in performing third-party audits of their farmlands.

- Additionally, consumers attempting to understand the safety of food products face a deluge of information. Economists have explained that the food industry is particularly rife with information asymmetry between consumers and suppliers because it encompasses complex supply chains, assurance systems, and global markets.

As an example, Target states on its website that it maintains an “[e]nvironmental monitoring program for pathogen control” but provides no information on which exact pathogens it tests. Nor does Target clarify whether it tests for pathogens on all products or just a subset.

- Finally, what happens to someone who only has access to one private grocer, and that grocer provides no clear guidance of its food safety measures at all?

Ultimately, testing by private grocery retailers may help some individuals avoid foodborne illness, but it cannot replicate all FoodNet’s benefits.

An active surveillance system enables states to respond to novel food safety issues, transform into laboratories of food policy, and advance the goals of American federalism.

To ensure that Americans remain protected from outbreaks, health officials in states with robust active surveillance programs should consider forming multi-state partnerships to aggregate information about the six pathogens removed from FoodNet. This collaboration can make up for any loss of data due to FoodNet funding cuts by including states that were previously outside of FoodNet’s network. Now that the federal government has withdrawn from longstanding food safety programs, states have the opportunity to lead.