Countering Moralizing Language in Medicaid Work Requirements

When does a person deserve to remain unhealthy?

Published

Author

Share

When does a person deserve to remain unhealthy? This question may sound cynical, even cruel. Yet longstanding political divisiveness in Medicaid eligibility presents an opportunity to resolve a longstanding tension in health policy: the imposition of moral weight to health and disease through harmful language in policy discussion about access to health care.

Debates over Medicaid work requirements suggest that the tone and tenor politicians and policymakers use in public discourse carry an implicit moral message. Even aside from the actual policies, moralizing language creates a dividing line between the deserving and undeserving sick, which reduces access to life-saving care and degrades our empathy.

A Descriptive Framework for Health and Morality

Societies have long moralized illness. From early Christian theology, which linked disease to sin, to 19th century public health campaigns that equated hygiene with virtue, the boundaries between health and moral goodness have rarely been clean. When disease appears random (i.e., when wealth cannot purchase immunity) moralization recedes. But when illness can be plausibly tied to behavior or poverty, judgment creeps back in.

Access to care, particularly for low-income people, is too often framed as a moral point of contention. Medicaid expansion debates, welfare reform, and personal responsibility provisions reflect a persistent view that those who need help must prove worthy to receive it.

How policymakers communicate matters as much as what is legislated. Words have power. They encode moral hierarchies. They shape who is humanized and who is reduced to an administrative category. By being conscious of how we characterize others, we take steps away from identity-based politics and toward a more equitable future.

Medicaid Work Requirements

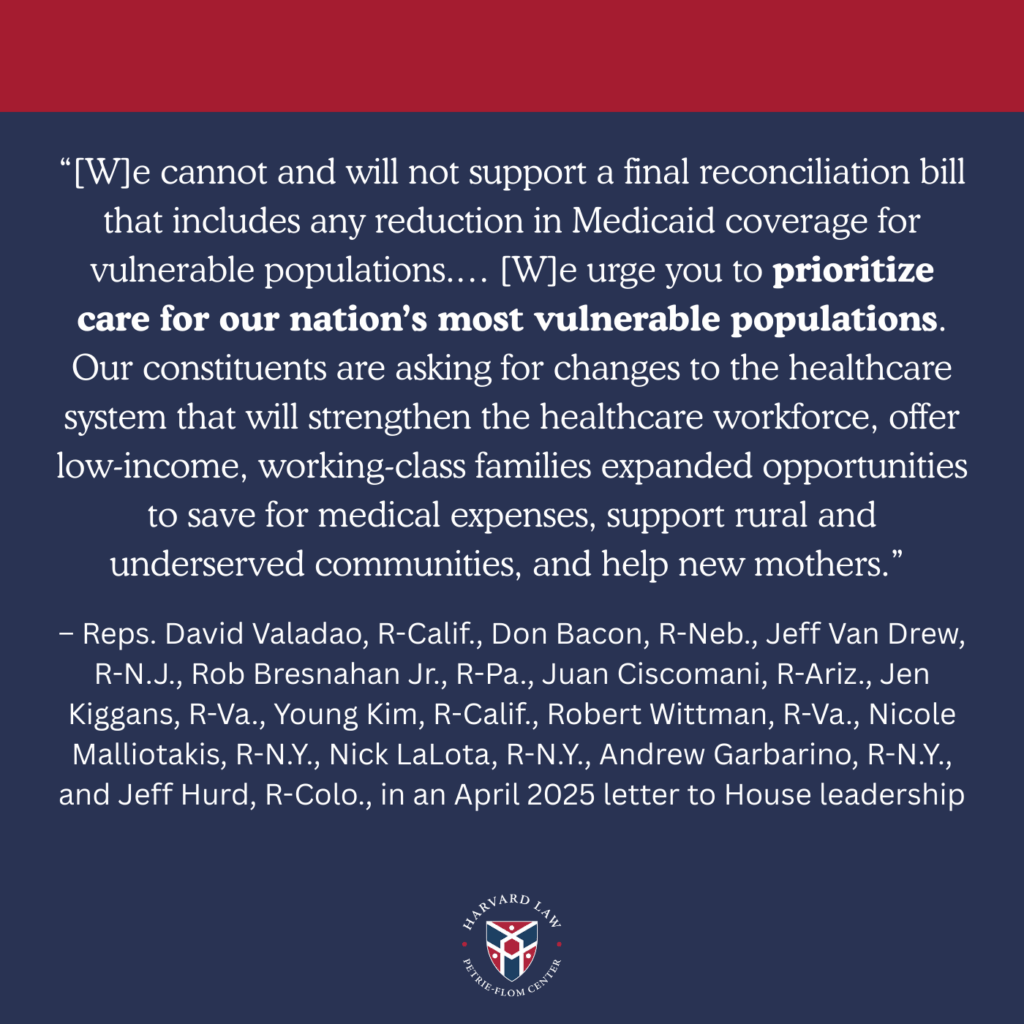

Few contemporary policies illustrate moralizing language as clearly as the recent Medicaid Community Engagement Requirements (aka, work requirements) in the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB). The Medicaid eligibility debate is often couched in the language of accountability and fairness, suggesting that health coverage is something to be earned. Under the OBBB, Medicaid eligibility is conditioned for so-called “able-bodied” individuals ages 19-64 on working or participating in qualifying activities for at least 80 hours per month. If the state is unable to verify, the beneficiary will be disenrolled from Medicaid.

Many ultraconservatives justify Medicaid work requirements by highlighting that deserving Medicaid recipients will no longer be crowded out by 35-year-old gamers living at home, using rhetoric reminiscent of Ronald Reagan’s “Welfare Queen.”

Examples of Dehumanizing Language

The Medicaid work requirements are expected to reduce federal spending by $326 billion over 10 years, primarily through disenrollments. But whether or not work requirements make fiscal sense is a separate aspect of the debate (especially when a significant portion of the savings is likely to be attributed to administrative burden and error). All stakeholders should take issue with the tenor of the conversation. It invites policymakers and the public alike to view lack of access to care (and, relatedly, poverty) as a personal failing, rather than as an economic and structural condition.

When we describe people as burdens, cost-drivers, or freeloaders, we not-so-subtly rationalize exclusion. For those impacted by Medicaid work requirements, that exclusion is largely undeserved: According to recent KFF report, nearly two-thirds of Medicaid enrollees under 65 are working, and roughly three in 10 are out of the workforce due to caregiving responsibilities, illness, disability, or schooling.

The Work of Language

Language will not, on its own, reform Medicaid policy. Meaningful change requires a multifactorial and nuanced rethinking of insurance design, eligibility, and benefit adequacy. Yet identifying where our words carry moral residue is a crucial starting point. By choosing language that conveys compassion and empathy, we affirm the inherent worth of our most vulnerable community members.

Examples of Humanizing Language

Science continually reveals the complex interplay between biology, environment, and socioeconomic status, factors far beyond individual control. In light of that understanding, vestigial sensibilities about who deserves to be healthy should be reexamined. A critical first step is to deconstruct the moralizing language policymakers often use to disparage Medicaid beneficiaries.

Access to health care should never be a moral verdict.