The Fight for Mental Health Is the Fight for Human Rights: Argentina’s Movement for Dignity and Inclusion

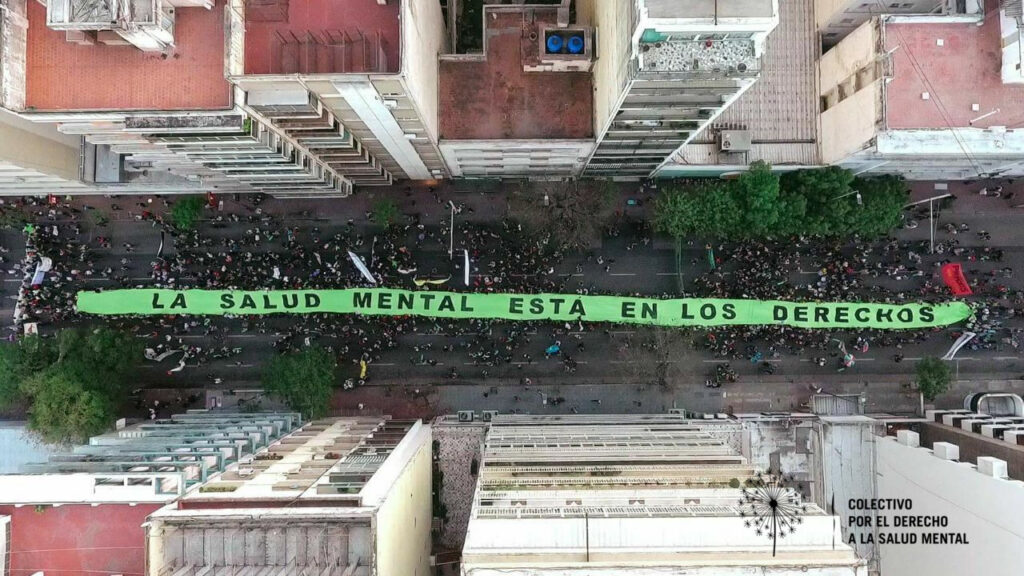

In Argentina, austerity threatens hard-won progress in mental health. In Córdoba, the 12th March for the Right to Mental Health filled the streets with color and conviction — reminding us that mental health is built through rights and sustained by care, equality, and community.

Published

Author

Photo credit

Collective for the Right to Mental Health of Córdoba

Share

In Argentina, austerity threatens hard-won progress in mental health. In Córdoba, the 12th March for the Right to Mental Health filled the streets with color and conviction — reminding us that mental health is built through rights and sustained by care, equality, and community.

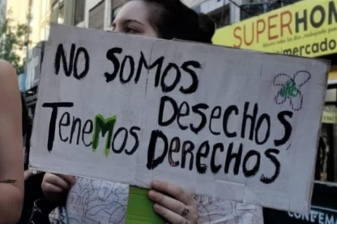

On Oct. 31, the city of Córdoba hosted the 12th March for the Right to Mental Health. Under the slogan “We are not waste, we have rights,” thousands of people took to the streets to demand the effective fulfillment of the right to mental health in Argentina — at a time when budget cuts and policy setbacks threaten the fragile progress achieved over the past 15 years.

The march was organized by a broad and diverse coalition that included users of mental health services, family members, professionals, social and student organizations, human rights groups, labor unions, and professional associations. For 12 years, this collective has built shared diagnoses and articulated demands to make visible that mental health is not merely an individual or medical matter, but a fundamental component of human rights and social justice.

Policy Backsliding in Argentina’s Mental Health System

In 2025, Argentina marks 15 years since the enactment of National Mental Health Law No. 26,657, a landmark reform that incorporated international human rights standards and promoted the gradual replacement of psychiatric hospitals with community-based care models. Yet progress in implementing the law has been uneven and limited across provinces.

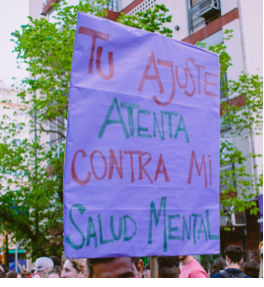

Moreover, the national budget proposal for 2026 foresees a reduction of more than 90 percent in funds allocated to the implementation of the Law. This drastic cut — combined with reductions in key areas such as health, education, housing, labor, and social protection — undermines the very possibility of guaranteeing basic economic, social, and cultural rights.

Global research has shown that austerity measures erode living conditions and generate psychosocial distress. In Argentina, these consequences are already evident. A report presented to the National Chamber of Deputies by senior mental health and addictions officials from 11 Argentine provinces revealed that in 2024, psychiatric hospitalizations increased by 10 percentage points compared to 2023, while outpatient mental health consultations rose by an average of 78.5 percent. The report also noted rising levels of anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and greater consumption of psychoactive substances, as well as an increase in self-harm, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

This exponential rise in psychological distress and demand for mental health care has fallen primarily on the public sector, which faces severe underfunding. The deregulation of private insurance providers and the rise in unemployment and precarious labor have driven thousands of people toward public hospitals and clinics that are already overwhelmed. This creates a vicious cycle of crisis that undermines human rights and psychosocial well-being: more suffering, fewer resources, greater inequality.

Human Rights Obligations and Regional Commitments

Argentina is not only confronting a public health crisis but also a crisis of compliance with its international human rights obligations. Budget cuts disproportionately affect people in situations of vulnerability — older adults, persons with disabilities, and children and adolescents — violating the principles of equality and non-discrimination.

The right to mental health, understood in a comprehensive and inclusive way, requires that the State ensure both the social determinants of health and access to care that is timely, adequate, affordable, non-discriminatory, and of quality.

At the regional level, the Panama Consensus (2010) committed Latin American and Caribbean States to transform their mental health systems and to eliminate psychiatric asylums by 2020. Although Argentina has made progress — such as halving the number of long-term psychiatric hospitalizations— the path toward full deinstitutionalization remains incomplete. Closing asylums must go hand in hand with creating sustainable, community-based services that allow people to live independently and with dignity. This is another one of the central demands highlighted by the march.

A Struggle for Dignity and Inclusion

The March for the Right to Mental Health also denounces new forms of discrimination against persons with disabilities and users of mental health services, in a broader context of rising hate speech and stigmatization in Argentina. Against this backdrop, the movement asserts a powerful message: We are all potential users of mental health services, and we all have the right to be treated with dignity.

The march, which continues as an ongoing movement rather than a one-time event, is therefore not only an act of protest but also one of collective celebration: colorful, joyful, and filled with banners and chants calling for a more just and inclusive society. Each year, in the streets of Córdoba, participants renew a shared commitment: to ensure that mental health is no longer seen as “a matter for the insane,” but, finally, as a matter for us all. Moreover, the march reminds us that mental health is not only a right — it is embedded in all rights. To fight for mental health is to fight for dignity, equality, and the realization of all human rights.

Video of the march is available here.